The Result of an Authoritarian Structure

Three factors compounded to create the Inquisition, a dark era in the Catholic Church’s history (the narrative of which has been systematically rewritten to separate this event from the faith that spawned it) that would seem quite at odds with its other teachings. One is inherent to most religions, a type of “us and them” mentality caused when a believer thinks themselves irrevocably right, and all non-believers irrevocably wrong. The latter two however, were largely unique to Catholicism. It had a highly hierarchical and evidently authoritarian structure, and it wielded enormous power over both the individual and European kingdoms as a whole.

14th-century miniature from William of Tyre's Histoire d'Outremer. National Library of France, Department of Manuscripts.

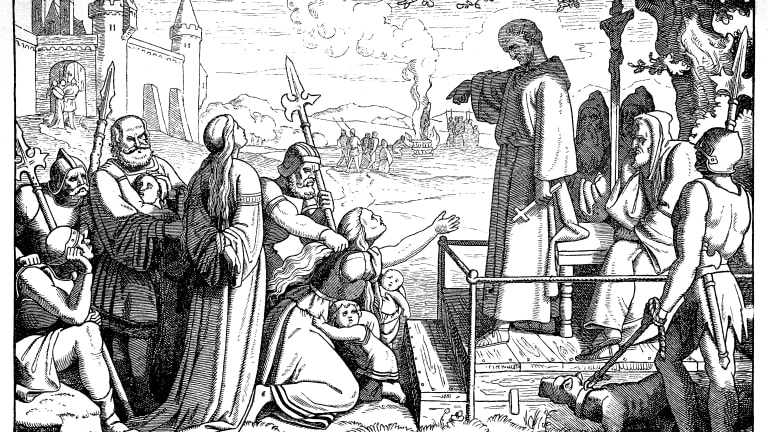

Berruguete, Pedro, Saint Dominic Presiding over an Auto-da-fe. 1493 - 1499. Museo Nacional del Prado.

The Inquisition as it Relates to Communication

The Inquisition was largely a means of retaining power and religious supremacy. Such oppression of dissent served as a method of communicating and reinforcing the Catholic Church's ideology and teachings. Toby Green goes as far as comparing the system of the Inquisition with that of the totalitarian governments that would later ravage Europe, saying “A secret police and a thought police, the Inquisition produced a permanent state of fear and invented an atmosphere of paranoia and institutional persecutions that created the precedent for totalitarianism” (Green, 2009).